To MLK, It Was Never About MLK

The Connection to Moses That Is Not Obvious, But Really Powerful

I posted this last year on MLK, Jr. Day, and I'm resending it now. My mailing list has about doubled since then (thank you all!) which means roughly 70% of you likely haven't seen it.

It's a good post for the beginning of another “only I can fix it”-style presidential campaign, and a reflection on what truly great, enduring leadership actually looks like.

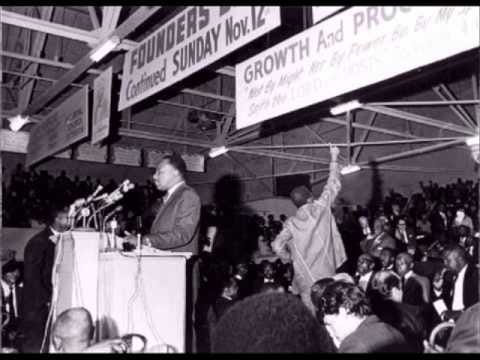

Today I re-read MLK’s final speech, “I've Been to the Mountaintop,” delivered August 3, 1968, in Memphis, with its electrifying, prophetic ending:

But it really doesn't matter with me now, because I've been to the mountaintop. And I don't mind. Like anybody, I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I'm not concerned about that now. I just want to do God's will. And He's allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I've looked over. And I've seen the Promised Land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land! And so I'm happy, tonight. I'm not worried about anything. I'm not fearing any man! Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord!!

Today I realized that there may be another powerful and telling Moses reference earlier in the speech, but it is much more subtle.

King references the 1958 assassination attempt that nearly killed him, and how his doctors had told him that he was a sneeze away from death, as the tip of the knife rested ever-so-close to his aorta. King listed the things he would have missed “if I had sneezed.”1

If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been around here in 1961, when we decided to take a ride for freedom and ended segregation in inter-state travel.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been around here in 1962, when Negroes in Albany, Georgia, decided to straighten their backs up. And whenever men and women straighten their backs up, they are going somewhere, because a man can't ride your back unless it is bent.

If I had sneezed -- If I had sneezed I wouldn't have been here in 1963, when the black people of Birmingham, Alabama, aroused the conscience of this nation, and brought into being the Civil Rights Bill.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have had a chance later that year, in August, to try to tell America about a dream that I had had.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been down in Selma, Alabama, to see the great Movement there.

If I had sneezed, I wouldn't have been in Memphis to see a community rally around those brothers and sisters who are suffering. I'm so happy that I didn't sneeze.

It hit me for the first time today that King assumed in his speech that all of these things would have happened even without him. This section of the speech parallels the first part, when he lists all the different historical eras God could have placed him within rather than mid-20th century America. King is not thanking God for the opportunity to have led the civil rights movement that may not have happened without him. He is thanking God for the opportunity to have witnessed it.

I imagine that this is how King was so sure that his people would get to the promised land without him - because he wasn’t the heroic redeemer who got them to its border in the first place. He was the one who was blessed to encourage them with his vision from the mountaintop, but they were the ones who got there.

This is not an obvious move. It speaks volumes first about King’s humility, but more significantly about his belief in the civil rights movement as a genuinely popular movement. It is especially striking in retrospect when our historical sense of the civil rights movement and its accomplishments kind of telescopes around King as a Great Leader.

The more I think about this, the more I think about the famous question posed about the near-complete absence of Moses’ name from the Passover Haggadah despite being the central character in the story of the Exodus.

There are many answers that attempt to resolve this glaring omission (here are just a few). One might be that the Exodus would have happened even without Moses. Moses senses this from the beginning, which is why he asks God to send someone/anyone else.

[The Targum Yerushalmi, an early translation/commentary on the Torah, suggests this approach as well. The last verse of Exodus chapter two reads:

וַיַּרְא אֱלֹהִים אֶת־בְּנֵי יִשְׂרָאֵל וַיֵּדַע אֱלֹהִים׃

God saw the Israelites, and God knew.

But what did God see, and what did God know? The Targum “translates” into Aramaic:

וַחֲמָא יְיָ צַעַר שִׁעֲבּוּדְהוֹן דִבְנֵי יִשְרָאֵל וּגְלֵי קֳדָמוֹי יַת תִּיוֹבְתָּא דְעָבָדוּ בְּטוּמְרָא דְלָא יָדְעוּ אַנַשׁ בְּחַבְרֵיהּ

And the Lord looked upon the affliction of the bondage of the sons of Israel; and the repentance was revealed before God which they exercised in concealment, so as that no man knew that of his companion.

In other words, something had shifted, imperceptively to everyone but God, and the people, even if they did not recognize it yet in themselves, were ready to be redeemed. The very next verse begins chapter 3 and the narrative of God calling on Moses at the burning bush, as if to emphasize that Moses was not being called upon to mobilize the people so much as he was being called to a people that was already ready and waiting to be redeemed.

I am not aware of Dr. King citing this particular interpretation, but it feels very close to what he meant by “Negroes in Albany, Georgia, decided to straighten their backs up,” in 1962, explaining, “…Whenever men and women straighten their backs up, they are going somewhere, because a man can't ride your back unless it is bent.”]

There is something to be said here about the Great Man v. bottom-up theories of history, and we can quote Carlyle, Marx, Zinn, and all the rest. It’s a classic debate, but I think that the real point is that King (and Moses) themselves refused to see rigid hierarchies. Their movements weren’t their movements, but movements of which they were a part, just like everyone else, and they succeeded or failed as a group, not as leaders pulling along their flocks.

As Moses said to God, anyone else could have been the leader. King was happy to have experienced it, not to have done it.

Moving more into theology, the more seriously you believe in the innate dignity (Divine Image) of each individual, the more you wind up taking the King (Moses) perspective. The less seriously you take it, the more you wind up with a vertical hierarchy of a leader and followers in which only the leader is fully humanized and the followers tend to be objectified.

Not only does the former approach describe the leadership style of King (and Moses), but it also describes the ideals that he (they) aspired to. It is no wonder that King, in particular, built his movement around voting rights - not just for the raw political power it would afford his followers, but for the theology that democracy, at its most idealistic, represents.2 (Raphael Warnock, King's successor at Ebenezer Baptist Church, calls democracy "the political embodiment of a spiritual idea.")

Another explanation offered for why Moses’ name is omitted from the Haggadah is that the Exodus is meant to be seen less as a singular event in history accomplished by a particular person in a particular setting and more as a template. There was only one Moses, but, in every generation, we are constantly leaving Egypt.

Similarly, today is certainly a day to celebrate and reflect upon Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s unique, brilliant life and achievements. But those achievements themselves speak to the principles that guide us past King the historical personality to the ongoing work that continues, certainly to our day.

This is really pushing it, but in the Midrash sudden death is referred to as death with a sneeze. According to rabbinic legend, this was how all people died until Abraham, who was the first person to visibly age and therefore receive the respect due to an elder.

It is also no wonder why God and the prophet Samuel are both less than thrilled (and see an element of rejection) when the Israelites ask for a king.

Thank you